Getting there! Still needs a bit of reshaping, and I need be able to put all the points I make into a real question. Obviously still need to reference everything as well.

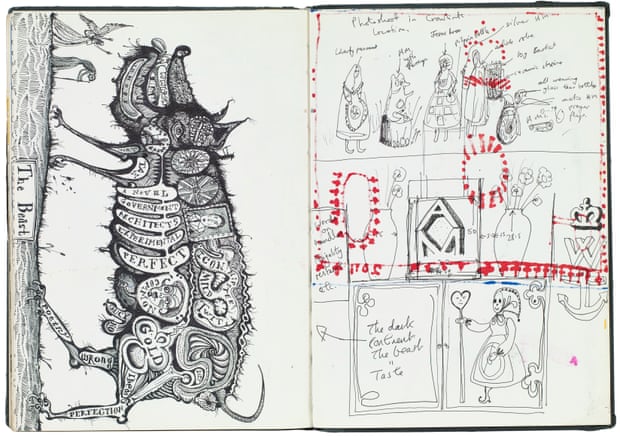

“Playing to the Gallery”: Grayson Perry and the (in)accessibility

of the Art World

Delivering the first of his 2013 BBC Reith Lectures, Grayson

Perry , one of Britain’s most visible and – certainly – most beloved artists,

reminded his audience, to raucous applause, that his series of lectures were to

be entitled ‘Playing to the Gallery’

and not ‘Sucking up to an Academic Elite’.

This mischievous jibe at the artists, learned academicians and cultural and

intellectual institutions that we shall here refer to as the ‘Art World’ is

symbolic of what has so endeared Perry to the general public, a kicking back

against an establishment that can, at best, be said to seek a certain

intellectual distinction from the masses and, at worst, be said to actively and

deliberately alienate or baffle them. Does it matter, then, that Perry’s

comments come from a man who is a self-admittedly “paid-up member of the art establishment”? Perhaps not. A fervid dismissive

of the notion that the opportunity to appreciate and enjoy art should be

exclusive, Perry has become the acceptable face of contemporary art, while

retaining his subversive edge. Never patronizing or purposefully oblique, he is

instead friendly, witty, punchy and self-deprecating; in short, everything that

contemporary art is often not. This essay considers some of the ways in which

the contemporary Art World may appear unavailable to the everyman, and the role

of Perry, now such an embedded fixture in the cultural landscape of the nation,

as the antithesis to this elitism.

Grayson Perry occupies a unique place in the British

collective consciousness. Both as an artist – his exhibitions tend to be

sell-out successes – and as a maker of some of the most applauded and

thought-provoking television in recent memory, he seems able to break down

barriers of communication in a way that contemporary artists seldom seem to.

The accessibility of Perry’s discourse is a rarity in a cultural field that is

often dense and unhelpfully lacking in clarity. In truth, the language of The

Art World is, quite literally, foreign. In 2011, Alix Rule, a sociologist and

linguist , and David Levine, a graphic designer, embarked upon an experiment,

supported by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, to analyse the

unique lexical, grammatical and stylistic tics of an increasingly

internationalised Art World. Rule and

Levine believed the purest articulation of this language to be found in the

digital gallery press release. The nexus of online communication in the Art

World is e-flux, a listserv that distributes approximately three announcements

per day about art-events worldwide. In the years since its 1998 launch, the

digital archives of e-flux have accrued a corpus of texts substantial enough to

give an accurate representation of patterns of linguistic usage. All thirteen

(then) years’ worth of e-flux press announcements were entered into Sketch

Engine, a language analysis programme that allows the user to analyse language

usage in any number of ways, including discourse structure, word usage over

time, and syntactical behavioural patterns. What was spat out of Sketch Engine

at the end of this vast study is something quite extraordinary; an almost fully-formed

language, a language with its own grammatical rules, syntactic codes, and

distinctive lexicon. This language was given the title International Art

English (IAE), and it is identifiable as the Art World’s “universally foreign language”. Rule and Levine defined this

language as one that “has everything to

do with English, but (it) is emphatically not English”. IAE reclaims and

subverts existing words, in some cases cleaving them completely from their accepted

meanings. Stylistic features of IAE include elongated sentences, an odd

mishmash of past and present participles, and a liberal usage of adjectival

forms. Although no one would deny its distinctiveness, not having its own

specialist terminology means that IAE cannot be a mere technical vocabulary. IAE

is not comparable with, for example, the

specialized English of the auto-mechanic

when he talks of ‘balancers’ or ‘gauges’: While his jargon may be slightly lost

on someone who doesn’t share his understanding of the field, the semiotics of

his language are not so far dislodged as to become incomprehensible. As Rule

and Levine argue “by referring to an

obscure car part, a mechanic probably isn’t interpellating you as a member of a

common world … He isn’t identifying you as someone who does or does not get it”.

The primary function of IAE is as a way of identifying the user as a voice of

authority in the Art World, a primitive signal passed to other IAE speakers

that the user is ‘one of them’. The real question (of course, a subjective one)

is whether or not IAE actually carries any kind of intellectual seriousness, or

whether it is simply the Art World’s equivalent of management speak, needlessly

opaque blather employed to scare the little people out of the galleries. In the

interest of balanced discussion, let us draw a defence of IAE by referring to

Wittgenstein’s talking lion. If we accept that language is only rendered

intelligible by all participants in a dialogue having an understanding of the

social, political or academic backdrop against which it is employed, then it stands

to reason that active members of the Art World, those educated in the either

the practise or the theory and philosophy of art would communicate about the

subject on a different level to the casual gallery visitor, someone with

perhaps limited access to contemporary art, for reasons geographical or

otherwise. Why then is IAE defined not by its use of a specialised or technical

vocabulary, like the aforementioned mechanic, but by its tendency to use

recognizable elements of the English language in a completely unrecognizable

way? Can such an act be anything other than intentionally alienating? The

impenetrability of this particular brand of linguistic weirdness means that the

non-fluent in IAE might question their own judgement of art, believing that

they need to understand all this in order to justify their emotional or

intellectual responses to works of art.

In a welcome hymn to 21st Century inclusivity, Perry assures

his audience that they needn’t. A rather more enjoyable explanation of IAE can

be supported by Stephen Pinker’s Blank

Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2003). Pinker argues the

existence of what he coins a “baloney

generator”, essentially a face-saving device in the left hemisphere of the

brain. According to Pinker, the function of this device is to weave coherence

out of chaos, enabling us to create an ad-hoc explanation for every thought we

have, and every behaviour we exhibit; these explanations are often totally

untrue. Should we be called upon to justify ourselves to anybody, these

generators will kick in, preventing us from staying foolishly mute, even if we

have no conviction in what we are saying. While experiencing Rule and Levine’s

“metaphysical seasickness” when

reading IAE, it is easy to suppose that the entire discourse surrounding

artistic practice is little but saving face en-masse.

Since the emergence of the cluster of individuals commonly

referred to as the ‘young British artists’ (yBas) onto the British art scene in

the early to mid-1990s, exposure of contemporary art via the mass media has

increased exponentially (as an interesting aside, Perry’s Reith Lectures, the

first to ever be delivered by a fine artist, attracted the highest recorded

listening figures in the history of the flagship series). In High Art Lite: The Rise and Fall of Young

British Art, Julian Stallabrass recognises this period as being the point

at which the traditional notion of the artist began to dissipate, and the

artist was repackaged as an “artist-personality”

- a glossier, showier, sexier reincarnation of what had been before, in which

art, image and celebrity combined. Stallabrass sites influential artist-duo

Gilbert and George, whose synchronised existences seem to be a continuous

performance art-piece, as a prime example of the artist-as-celebrity, but notes

those most famous figureheads of the yBa generation, namely Damien Hirst and Tracey

Emin, renowned for their celebrity hobnobbing in London’s Groucho Club, as

equally effective examples. Even Grayson Perry is as knowable to the public for

his transvestism, and the bawdy jollity of his public persona, as his output.

But does this re-emergence of the artist

as a public figure, whose recognisability is measurable in column inches, mean

that the pursuit of art itself is more inclusive and digestible now than it has

been previously, or that, just like the artists themselves, the elitism

surrounding the Art World has been simply reshaped somewhat. When considering

the role that this new generation has played in the opening up (or not) of the

Art World to the masses, one must consider the way that the artwork of this era

was presented to the world, and not just the artists themselves. Although it is

easy to fixate on what artefacts are

exhibited in art-spaces, it may be more conducive to discussion on the

inclusivity or exclusivity of contemporary art to also consider where and how these artefacts are displayed. If the gallery as we

traditionally recognise it – walls filled with paintings, halls filled with

sculpture - is intimidating in its cultural-historical gravitas, then one would

think that the reclamation of disused and desolate spaces by the yBas, most

famously the abandoned block in London’s Docklands that housed 1988’s Freeze, an exhibition that has since

achieved near-mythical status, were an injection of freshness into a British art

scene that was, at the time, largely stagnant. These were young artists,

turning their backs on the elitism incarnate represented by the traditional

gallery establishment, right? Wrong, argues Stallabrass, claiming that the

excitement of these shows was itself “bound up in implicit elitism”. Housing

exhibitions of work in functional, industrial spaces was less a statement about

giving art back to the communities around these emphatically not art-spaces, and more a tactical

side-stepping of the defunct apparatus represented by private galleries (that

financial recession had hit hard) and assumed philistinism of public-sector

galleries, that were not deemed ready for what these supposed radicals had to

say. Stallabrass goes on to point out that however subversive and apparently

open this approach to exhibiting art may seem, that all those involved, Hirst,

Emin et al, had been through the formal channels of art education, most coming

from the sophisticated Fine Art course at Goldsmiths, and as such were schooled

in the high theory and history of the avant-guard. These exhibitions were still

exclusive, albeit a new manifestation of exclusivity. Describing the cultural

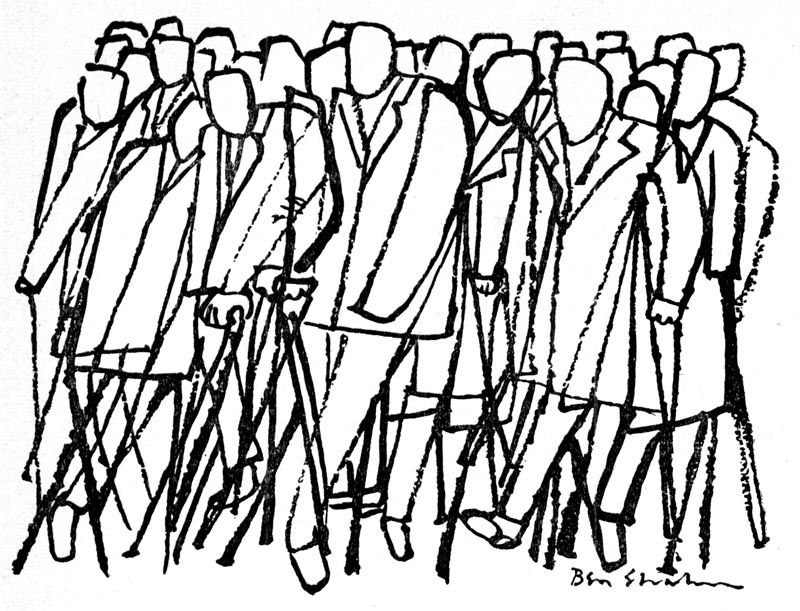

buzz of these new exhibitions, Stallabrass notes:

While the private

views of these exhibitions were sometimes crowded, the audience was a highly

homogeneous one – an invited elite-to-be. Everyone knew everyone else, or at

least knew someone who knew everyone else. The art, the exhibitions, the social

scene that accompanied them seemed to be all of a piece, and you bought into it

entirely or not at all.

If we are to concede with Stallabrass here, we must both accept

that the step taken by the yBas away from the conventions of the British art

scene was not a serious attempt to open up an elitist institution to the more

casual observer, and nor did it claim to be. This moment in time was merely

when British art and its (now) famous faces, became commodified, and mutated in

the grip of consumer and celebrity cultures. It may have become more available and visible, through the unrelenting and deeply interconnected web of

the mass media as we now know it, but this does equate with genuine

accessibility.

Although the new faces of British art made their impressions

outside of the public-sector gallery sphere, it is still through these outlets

that most casual art-enthusiasts or occasional gallery visitors will find a

narrow entrance to the Art World. Both the National Gallery and the Tate Modern

pride themselves of being among the most visited attractions in the world. Footfall figures may help public-sector

galleries justify their funding, yet high visitor numbers are not necessarily

an accurate depiction of a public and a contemporary Art World at one with each

other. In fact, as Perry points out in ‘Democracy Has Bad Taste’, the first of his four lectures, popularity with the public

is not seen as a hallmark of quality among the art establishment. He relays a

conversation he had with a distinguished curator of one of London’s major free

galleries, a conversation in which said curator remarked that David Hockney’s

‘A Bigger Picture’ show, held at the Royal Academy in 2012, was “among the worst she’d ever seen.” ‘A

Bigger Picture’ was the most successful exhibition of the year, drawing

record-breaking crowds. Critical reception to the show was lukewarm. Here we

see a discrepancy between what art the public might respond to, and what art

the art establishment feels is good for it. The power-politics that govern the

Art World is perhaps one of the most alienating things about it. Access the

public has to art has inevitably been designed and determined for them. While

it can be argued that the public still have the critical autonomy to respond to

the art they are exposed to, they have none when it comes to what that art is. The

question of what art is displayed in galleries is not open to democratic

referendum; these are curated spaces, and every work in them, whether “object or non-object” has already been through

a series of unofficial juries at private views, auctions, and fairs. The role

of the validator is an indispensable one in the world of contemporary art,

because its values and criteria are fundamentally intangible, or metaphysical.

As such, the ability to evaluate works of art, or at least the appearance of said ability, becomes the

ability to decide what is to be considered good art. The necessity for a work

of art to undergo a process of validation before the public have access to it

brings us to an important question: who validates? The answer is an ensemble

cast of Art World characters: certain artists, certain curators, certain

critics, certain collectors. These are the people who deem whether or not a

particular artist and their oeuvre is worth our while. The public gallery may

be the closest thing to a direct channel into the Art World that the general

public has, but this is not to say that the public hold any influence over what

is offered there. In his essay Network: The Art World Described as a System,

the art critic and curator Lawrence Alloway neatly summarises the roles

available within the contemporary Art World:

The roles available

within the system, therefore do not restrict mobility; the participants can

move functionally within a cooperative system. Collectors back galleries and

influence museums by serving as trustees or by making donations; or a collector

may act as a shop window for a gallery by accepting a package collection from

one dealer or one adviser. All of us are looped together in a new and almost

unsettling connectivity.

In this model, the public represent passive recipients of

the opinions and tastes of a governing body, a body with its own hierarchy and

criteria. The Art World can operate as a closed circuit, and need not rely on

the participation of the general public to continue to do so.

The question of who decides what art is worth our seeing,

leads us to the rather trickier one of who decides what art is art at all. At

first, this may seem a redundant question, as most of us have at least some idea of what we believe to be art.

However, upon more thorough and objective consideration, many of us would

probably decide that it is very difficult to define what art is, especially contemporary art,

irrespective of our own experiences or sentimental attachments. In the second of his Reith lectures, ‘Beating

the Bounds’, Perry states that “quite

often you can’t tell if something is a work of contemporary art apart from the

fact that people are standing around it and looking at it.” In just over a

century, ‘art’ – what it is, what it means, and who makes it – has undergone a

rather considerable theoretical revision. Until the late nineteenth Century,

art was largely a quest for beauty. Art for visual pleasure could be validated

in accordance with ancient Greek philosophy and culture, which is inclined to beauty

worship. Leo Tolstoy, writing in What is

Art? (1897), perceived the genesis of aesthetics, a thread of philosophical

inquiry concerned with notions of taste and the appreciation and creation of

beauty, to be rooted in the Renaissance.

For many, the masterpieces of the Italian renaissance remain the paradigm

of artistic achievement, with almost all taking the form of one of the three

classical pillars: drawing, painting or sculpture. Tolstoy, however, goes on to

dismiss the legitimacy of ‘beauty’ as a criterion for distinguishing good art

from bad art, suggesting that is in fact the idea, thought and feeling, behind

a work of art that validates it:

According to which

the difference between good art, conveying good feelings, and bad art,

conveying wicked feelings, was totally obliterated, and one of the lowest

manifestations of art, art for mere pleasure - against which all teachers of

mankind have warned people - came to be regarded as the highest art. And art

became, not the important thing it was intended to be, but the empty amusement

of idle people

Tolstoy’s writing on the subject can now be read as an

allusion to what would happen to the concept of art in the 20th Century, how it

would become subverted and warped beyond the point of recognition. On his 1917

‘Fountain’ Marcel Duchamp, the father of modernism and conceptual art, stated

that “the danger to be avoided lies in

aesthetic delectation” (at least, according to Danto.) The ‘readymades’ of

Duchamp – including, as well as the infamous urinal, a bottle rack and a comb –

represent a new landscape in contemporary art, completely at odds with what art

had once been, and bereft of any recognizable criteria against which to measure

it. The first known definition of a ‘readymade’ appears in Paul Éluard’s and

André Breton’s Dictionnaire abrégé du

Surréalisme (1938) as follows: “An

ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of

an artist”. We now arrive at a crux in the development of contemporary art,

where it appears that all recognizable parameters surrounding the question of

what art is are blown wide open. Nearly one hundred years on, Perry would

suggest that this is when art reached its “end-state”,

the point at which anything could be art. Surely then this should be the point

at which art becomes impossible to define in terms more specific than

‘anything’; but is that really the case? Cultural radicals such as Duchamp may

have set in motion the transformative idea that anything can be art, but it is

still the old definition that exists predominantly in the minds of the masses.

To the lay-viewer, untroubled by the complexities of post-structuralist theory,

classical beauty – or, at least, a certain aesthetic agreeability - in art is

probably still a main concern, as could be something as obvious as

recognisability. Grayson Perry is an artist originally famed for his ceramic

pots, one of the most ancient and familiar of art forms, and in more recent

years for his sprawling, vividly coloured tapestries. Couple this with the fact

that Perry is self-confessedly obsessed with the middlebrow and the mundane,

the here and now of society’s behaviour, and as such a lot of his work features

signifiers we recognise and understand, such as explicitly illustrated

political hot potatoes, or Hogarth-esque parodies of consumer culture. Do we

simply like it because we can more readily understand it than a split calf in

formaldehyde, or a ceramic urinal?

In his essay ‘The Artworld’, (1964) published in The Journal

of Philosophy: Volume 61, Arthur Danto explores this issue, and ponders that most

inflammatory question of what makes art – well, art. “With this query”, writes

Danto, “we enter a domain of conceptual inquiry where even the native speakers

are poor guides: they are lost themselves”. When considering the role a figure

like Grayson Perry can play in easing a tense relationship between the general

public and the complicated hierarchy that constitutes the Art World, allow us

here to consider just what it is that renders Perry a more approachable,

acceptable face in this body. Superficially, his laurels do not separate him

from any other number of less approachable figures, such as the majority of

yBa; he is Turner Prize-winning, and also came from a specialist art-education.

He is what Danto would describe as a “native speaker”. However, unlike so many

of his contemporise, Perry extends his hand to the general public. He may not

be able to school the masses in Danto’s domain of “conceptual enquiry, nor does

he pretend to be able to, but he least invites us to be lost in this realm with

him, and to enjoy without the pressures of absolute understanding.